Investigations on Environmental Chemical Signaling Processes and Animal Navigation

Introduction and Overview

Understanding the mechanisms by which environmental chemical signals, chemical defenses, and other chemical agents mediate various life-history processes leads to important insights about the forces driving the ecology and evolution of aquatic and terrestrial organisms. Sensory perception of chemical signals profoundly shapes many different biotic interactions, such as predation, courtship and mating, kinship recognition, and habitat selection. For chemical signals released into the environment, establishing the principles that mediate chemical production and transport is required for interpreting biological responses to these stimuli within appropriate natural, historical contexts. Although they are widely recognized as having critical importance, with few notable exceptions, mechanisms by which environmental chemical stimuli mediate physiological and ecological processes remain undescribed. To embrace this challenge, my laboratory is developing new instrumentation and analytical techniques for identifying the structures and concentrations of bioactive molecules while measuring their distributions over the time and space scales relevant to chemosensory information processing. Through field and laboratory studies, we are devising new theories on chemical communication systems and their roles in mediating physiological functions and ecological interactions at individual, population and community levels.

Specific Research Contributions - Theory, Laboratory, and Field

Animal Dispersal and Habitat Colonization:

Habitat selection by larvae is one of the most important factors structuring marine communities and we are investigating interactions between waterborne chemical cues and hydrodynamic processes in establishing patterns of colonization by invertebrates. Our studies have provided unequivocal experimental evidence that dissolved chemical cues mediate settlement by marine larvae under hydrodynamic conditions found in natural habitats. For oysters and barnacles, small peptides (chains of amino acids) were isolated and identified as settlement and metamorphosis inducers using chromatographic and spectroscopic techniques. Mathematical models identified the quantitative structure/activity relationships between these peptide signal molecules, larval behavior, and development. Remarkably, the peptide cues are all structurally related to the carboxy-terminus sequence of mammalian C5a anaphylatoxin, a potent white blood cell chemoattractant. These results support an evolutionary link between the more primitive external receptors functioning in chemical communication of marine organisms and internal receptors for mammalian neuro- and immunoreactive agents.

Predator - Prey Interactions:

Previous studies on taxonomically diverse animals have established the general existence, and importance, of the olfactory sense in a wide variety of behavioral processes. Evidence suggests that the sense of smell mediates search in many organisms. Unexplored, however, are linkages between successful olfactory-mediated search and guidance mechanisms to the hydrodynamic environment (shear stress and turbulence). To establish interactions between hydrodynamics and chemoreception, we conducted laboratory and field studies on predatory success and search strategies of estuarine animals (crabs and snails). Search ability was extremely sensitive to small changes in bottom boundary-layer structure. In estuaries, hydrodynamic regimes are transitional between smooth- and rough-turbulent conditions (low and high turbulence, respectively). Chemosensory systems of crabs and snails extract information primarily from the more predictable hydrodynamically smooth flows. Our studies indicate that mechanisms governing the physical transport of odor signals can have profound influences on the development of sensory and behavioral mechanisms. Moreover, they also control biotic interactions such as predation, which in turn, can mediate community structure.

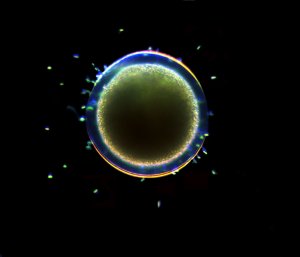

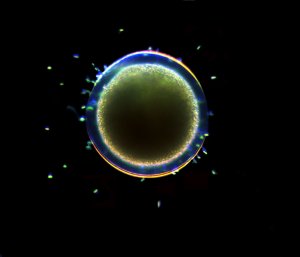

Chemical Communication and the Language of Sperm and Egg:

Chemically mediated behavior is a key component of sperm-egg dynamics, in habitats ranging from the turbulent ocean to a mammalian reproductive tract. Our recent discovery of the sperm attractants, bourgeonal in Homo sapiens and L-tryptophan in abalone (Haliotis rufescens), bridged the gap between molecular biology and fertilization ecology. In humans, a bourgeonal-sensitive, olfactory receptor protein (hOR17-4) is expressed exclusively on sperm membrane. Thus, sperm have a "nose". The receptor acts through a G-protein-coupled cAMP transduction pathway in regulating calcium uptake and sperm chemotactic responses. In abalone (a large marine mollusk), sperm detect shallow concentration gradients that develop when tryptophan is released naturally by an egg. The male gametes integrate chemosensory information over 200 ms and negotiate attractant gradients in laminar-shear flows by using helical klinotaxis to redirect swimming motions (rotational and translational velocities). Because human and abalone sperm navigate similarly, chemical communication apparently involves species-specific dialects of a common language at the molecular, cellular, and behavioral levels.

Heterotrophy and Biogeochemical Cycling in Microbes:

Behavioral responses by microbes to chemical stimuli are critical for nutrient cycling in marine environments. We have established the motility of mixotrophic protozoa in response to alternative nitrogen substrates, including amino acids, ammonium and nitrate. Significantly, cells were attracted to these substrates at concentrations naturally occurring in seawater. The patterns of motility in response to amino acids and nitrate were differentially expressed by genetically identical cells depending on the nutritional environment. The observed chemosensory behavior was consistent with cells maximizing their use of alternative nitrogen substrates under contrasting conditions of nutrient limitation. We have also investigated the responses of bacteria to biogenic sulfur compounds. Dimethylsulfide (DMS) is a predominant volatile substance emitted from the oceans to the atmosphere. It has been implicated as a major factor in regulating climate and in increasing the acidity of precipitation. DMS in seawater arises primarily via enzyme degradation of dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP), a substance produced in high concentrations by phytoplankton. Following induction to synthesize the degradation enzyme, bacteria were attracted to DMSP at levels occurring in seawater near senescing phytoplankton cells. In contrast, genetically identical cells without enzyme induction were not attracted to DMSP. We are currently testing whether the degradation enzyme, or a protein coinciding with it, functions as a chemoreceptor that mediates chemical attraction, or as a transporter for DMSP uptake from the environment across the periplasmic membrane. When combined with enzyme activity, bacterial attraction to DMSP should substantially increase the rate of DMS production and therefore play a critical role in biogeochemical sulfur cycling between dissolved organic matter in seawater and the global atmosphere.

Summary and Synthesis

Recent advances in technology now provide outstanding opportunities for new discoveries, thus allowing quantification of chemical signals in marine environments. My laboratory's past work on chemically-mediated interactions between organisms emphasized (1) habitat colonization, (2) predation, (3) chemotaxis and cell motility, and (4) chemical signal production and transmission. Current priorities include these same topics, as well as expanding work on predation to remote deep sea habitats while beginning new projects on parasite/host interactions, fertilization and sperm/egg recognition. By rigorously determining the effects of chemical signals on organisms under environmentally realistic conditions, and by integrating these findings within a larger ecological and evolutionary framework, we hope to contribute new theory and information on a wide range of topics in the marine sciences. Such broad integrations are intellectually and technically challenging, and our future research will include interdisciplinary investigations on numerous spatial and temporal scales.

Richard Zimmer - main

||

z@biology.ucla.edu