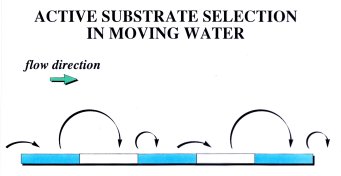

Our research over the last two decades has demonstrated passive and active stages to the settlement process. Larval supply to the bed is determined largely by hydrodynamics. Once they have contacted a surface in slow flow, larvae may reject it and swim upwards, or begin to examine the bed. Above a threshold turbulence level, however, larvae are physically prevented from settling or attaching to the bottom. After touching down, larvae investigate the surface and elect to stay or leave. Exploration generally occurs in the direction of the flow, and thus, fluid dynamics constrains habitat perusal. Moreover, site selection criteria apparently include aspects of the near-bed flow regime, as well as chemical and biological features of the substratum.

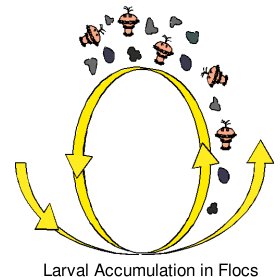

Most recently, our studies have implicated near-bottom flocculated material ("flocs") as a temporary venue for mature larvae and juveniles searching for a settlement site. In the field, larval densities were ten times higher in near-bed flocs than in plankton samples taken 1 m above the bed. Flocs usually contained larvae and juveniles of species that were abundant, as adults, in the underlying sediments. One of the most abundant species in flocs, however, was not historically or currently a member of the ambient benthic community. These larvae may have remained in flocs while searching for appropriate adult habitat. Flume experiments showed that larvae enter flocs actively in slow and passively in fast flows. Future experiments will determine if drifting flocs are a transient food-rich habitat that expose larvae to more potential settlement sites per unit time than would larval swimming.

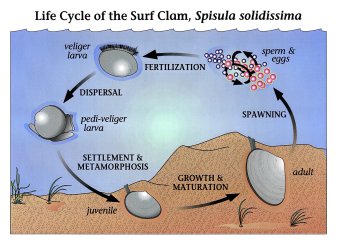

Larval dispersal

Planktonic larvae are unlikely to be randomly distributed over time and in space. Our initial settlement experiments were conducted in laboratory flumes because field estimates of planktonic larval availability could not be made at required temporal and spatial scales. In the early 1990's, I co-developed the first moored, time-series, zooplankton pump that could take 160 discrete larval samples, and was free from a surface power source. This pump, singularly or in spatial arrays, has successfully collected time series of larval concentrations in a variety of habitats, ranging from the shallow subtidal to the deep sea. The most extensive data set, thus far, is from a high-energy region of the coastal ocean known as the "inner shelf" (5-30 m depth).

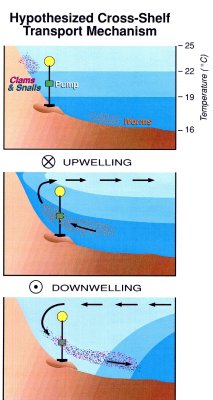

The inner shelf is a pivotal environment both physically and biologically. It is heavily impacted by human activities, but because of its inhospitable nature (energetic waves and currents), there is limited knowledge of oceanographic processes within this region. In 1994, we participated in an interdisciplinary study of cross-shelf larval transport off the inner shelf of the Outer Banks (NC). In vertical and cross-shelf pump arrays, the larval samplers were moored at depths similar to those of the physical instruments, thus sampling at comparable time and space scales. The purpose was to determine how larval distributions vary in time and space relative to the physics, and to identify processes most likely responsible for these variations.

The inner shelf is a pivotal environment both physically and biologically. It is heavily impacted by human activities, but because of its inhospitable nature (energetic waves and currents), there is limited knowledge of oceanographic processes within this region. In 1994, we participated in an interdisciplinary study of cross-shelf larval transport off the inner shelf of the Outer Banks (NC). In vertical and cross-shelf pump arrays, the larval samplers were moored at depths similar to those of the physical instruments, thus sampling at comparable time and space scales. The purpose was to determine how larval distributions vary in time and space relative to the physics, and to identify processes most likely responsible for these variations.

Prevalent patterns of larval variation could be explained by mechanisms involving active larval behaviors and passive physical processes. Time series from one vertical pump array, for example, showed two dominant scales of variability. A relatively high-frequency (3-6 h) signal could be partially explained by diel vertical migration. The pattern indicated larval ascent at night, perhaps to feed while avoiding visual predators, and descent during the day. Temporal variability at lower frequencies (2-10 d) reflected processes - transport by wind-driven cross-shelf (upwelling/downwelling) currents - that would ferry larvae long distances. Thus advected by strong along-shore and weaker cross-shelf currents, larvae zigzag up and down the coast while they feed and grow, vertically traversing the water column, and ultimately searching for a suitable habitat in which to settle.

Feeding strategies of adults

Studies of feeding strategies of suspension- and deposit-feeding organisms have revealed important and varied roles of hydrodynamic processes. Flume experiments using the suspension-feeding blue mussel, for example, tested a simple, two-dimensional advection-diffusion model of phytoplankton depletion above a mussel bed. In relatively slow flows, the vertical distribution of phytoplankton concentration generated by the model showed steep vertical gradients, with very low values close to the bed. Thus, feeding mussels depleted near-bottom water faster than it was replaced, via vertical mixing, with food-enriched water from the surface. In contrast, the vertical gradient in plant cells was more uniform in faster flow, indicating that downward mixing of phytoplankton-laden surface water occurred at a rate similar to that of mussel-bed consumption. Field measurements and flume experiments supported model predictions, both in the structure and magnitude of depletion. These results suggest that mussels distributed in relatively high-flow areas would have maximal food supply and growth rates.

Feeding strategies of foraging invertebrates also exploit the flow regime. Some deposit-feeding sand dollars live in highly mobile sediments that migrate as ripple fields in strong flows. Oriented horizontally, certain species burrow just below the sand surface and transport food (diatoms on sand grains) collected on their upper surfaces to their mouths underneath. Sand-dollars plow through the sediment via tiny moveable spines; locomotion is slow compared to typical transport rates of sand ripples. We thus hypothesized that migrating ripples would deliver more food (per unit time) to sand dollars than the animals could collect by active foraging. Sand-dollar locomotion was expected to decrease in moving ripple beds. Tracks of individual sand dollars were quantified in stationary versus migrating ripple beds in flume flows. The animals were tagged with insect pins bearing numbered flags that protruded above the sediment surface, and their paths video recorded. Replicate experiments revealed that animal movements were, in fact, considerably reduced in migrating ripple beds. Thus, both mussels and sand dollars should preferentially occur in high-flow areas, but for completely different reasons.

Current research and future directions

In addition to continuing research on near-bed flocculated material as a temporary venue for settling invertebrate larvae, we are involved in the following two research projects.

(1) Factors controlling local distributions of the "honeycomb" worm.

Along the coast of California, we have been quantifying spatial variability in local distributions of the highly gregarious, intertidal "honeycomb" worm (Phragmatopoma lapidosa californica). This species can form massive (meters to kilometers long), cemented sand reefs that stabilize beaches, so understanding the factors that create such features is of basic and applied significance. Through intensive field surveys, we have shown that patterns of worm distribution and size vary within rocks at a given tidal height, but differ between tide levels and geographical location. In the middle intertidal at Nicholas Canyon State Beach (Malibu), for example, worm aggregations are substantially larger on the back than the front of rocks. This pattern may be explained by passive transport of larvae and suspended food. As flow moves toward shore, recirculating eddies form on the shoreward (back) sides of the rocks. These regions would experience higher supply and retention of larvae and food (from offshore waters).

(2) Role of dissolved versus adsorbed chemical cues during settlement.

We are exploring the ecological relevance of chemical signal molecules and hydrodynamics in a remarkable biological system, where alternative cue types and larval developmental morphs occur within a single species and habitat. Larval behavior, transport and settlement are being studied for a small gastropod (Alderia modesta) that is common along the west coast of the United States. Producing two larval types (feeding and non-feeding) within the same population, larvae of this species also respond to dissolved and adsorbed forms of a carbohydrate produced by its obligate algal host (Vaucheria longicaulis). Thus, this biological system is internally controlled for several critical variables. This experimental field and laboratory flume study fills a critical void between large-scale supply-side processes and individual-scale exploration of the bed.

Cheryl Ann Zimmer - main || cazimmer@biology.ucla.edu